Growing up, my parents always told me that my Uncle Will was different. There was even a time that my mother said he suffered brain trauma from diving into the shallow end of a swimming pool1. It was later revealed that my uncle was, in fact, abused to a severe extent. I’m fairly certain he was also neurodivergent. I’m choosing to use that term for him instead of repeating the horrid things spoken about him and other folks like him in the decades of my childhood.

Uncle Will would often be at my grandparents’ house in Ohio when we visited. (Ooh, now there’s another complicated relationship; my mother never got along with her own parents.) Visits to that old house were chocked full of details in my memories.

My grandpa had a shop in the basement, an incredible array of old-school power tools like a lathe, a bandsaw, a planer, a radial arm saw. These were the kinds of tools that took four adults to heave them into position, and when he died, my mother gifted all of them to the next-door neighbor. I’m not sure how he got them out of that basement and into his own home, but they were legacy tools. I would have taken them with me, but it was impossible to figure out how to transport them across the country.

The kitchen was a disaster of cluttered countertops and spoiled food. I’ll spare you the description of sights and smells, but please, do let your imagination run wild.

A vacuum cleaner was always parked at the entrance to the living room. This provided the appearance of “we were just in the middle of cleaning for your arrival.” It’s been a humorous discussion point in my family for decades. Also important were the cleaning brush in the toilet bowl of the downstairs bathroom and the combs and brushes set in a bowl to disinfect.

The house itself was enormous. Built at the tail end of the 1800s, it boasted four stories plus a full-height basement. My brother and I would often explore the upper levels and recover treasures that we knew better than to remove. Imagine, if you will, a house built under layers of attics, each one a dangerous destination in itself, none of them easily accessible. Climbing over broken steps was a requirement. Cluttered piles of boxes, books, broken lamps, stretched bundles of wiring (possibly hot), abused furniture, heaps of clothing from long-gone eras, and stacks of kitchen implements created a landscape more similar to the surface of the moon than anything habitable.

The yard was a postage stamp of green grass with a single, towering tree. Please don’t ask what type; I only know it was sturdy enough to hang a swing from.

Beyond the yard was a garage, which had long since been turned into another shop, complete with even more tools, more storage, more of everything.

Now that you have the location in mind, on to the characters.

My grandfather was not a big man, but he was strong and wiry. He was also a charismatic asshole. His favorite thing to do when being introduced to someone was to clasp their hand firmly and proclaim, “What a pleasure it is for you to have met me.” And he was sincere about that. Imagine an entire personality built off of that statement, and you have my grandpa, Charlie. Charlie was a carpenter and a preacher. He felt that was a poetic combination (you can probably imagine why if you’ve been around protestant mindsets). I will spare you details of his “churching” exploits, but only because his ability to build with simple tools was far more interesting. He taught me many things about working with tools and wood, and he sparked an interest in building things in my young mind2.

My grandmother was only ever good at one thing, which was her incredible innate ability to play the piano. She could not read music at all. But if she knew the song or could guess it, she could play it in any key without difficulty whatsoever. Basic life skills? Those she did not have. She relied entirely on my grandfather for everything.

My mother is the youngest in the family. Her big brother, my Uncle Will, was the oldest. The big family conspiracy? We think there was a child in between them who did not survive. But, as was the case in the 1940s when things didn’t go well, the family did not ever discuss the missing child. There was no name provided, no birth date, no emotions expressed, nothing. We don’t really even know if a child was born at all.

My earliest memories of my uncle are of him playing the piano, probably songs he had written himself. He wanted to be a great musician, a creator of memorable tunes and melodies. When he played these songs I would usually ask my older brother if they were the Mr. Rogers theme song. They all sounded like that.

Will wasn’t good with jobs. He would work for a while at something only to be let go. Fired. Laid off. Pushed out of a job. The reasons may have changed, but there was a theme.

Once, when I was perhaps 8, my big brother 12, we were left in the care of my uncle at my grandparents’ house. For the guts of two hours he regaled us with stories.

They were the most incredible stories I had ever heard in my life.

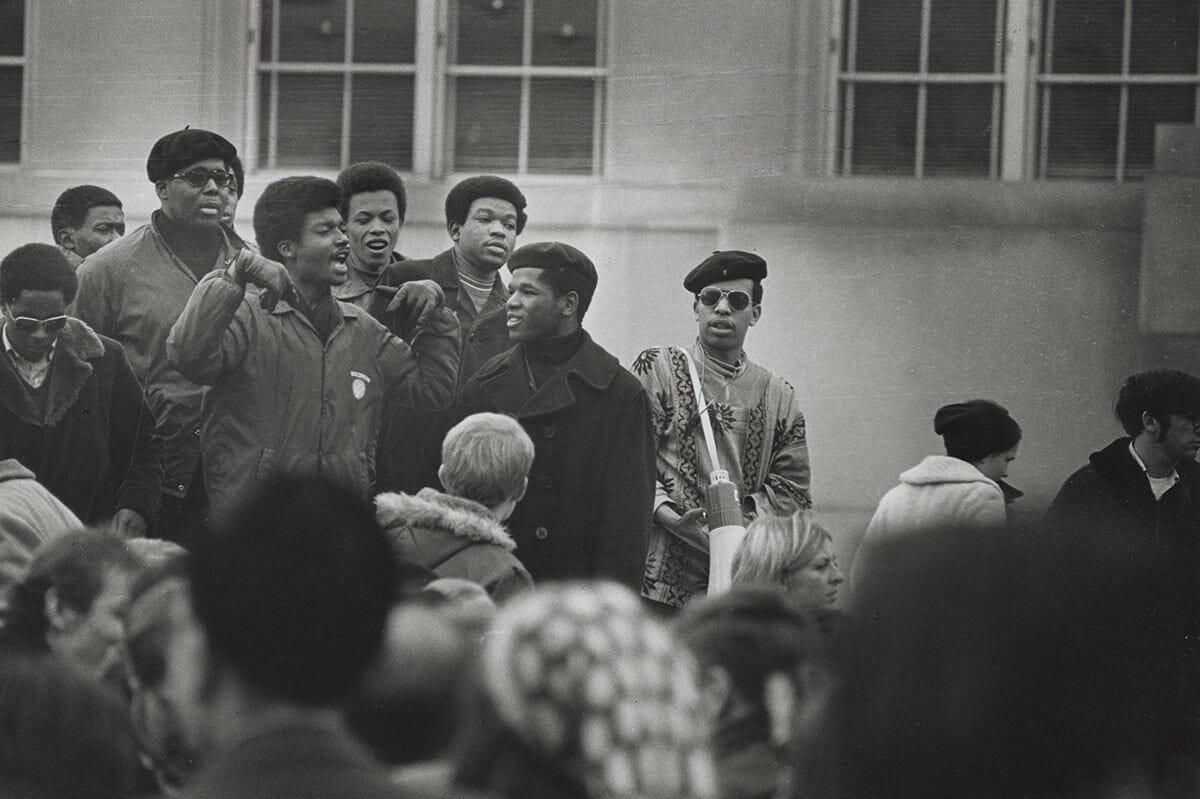

February 1969, UW Madison college campus, often called the Black Student Strike. While thousands of students and protesters were peacefully gathering to demonstrate for the attention of the school, my uncle stood at the perimeter of the crowd to take photos for a local newspaper. He was frequently hired as a photographer and news reporter for small-town papers in the 60s and 70s, but this was the most noteworthy story he had ever gotten to cover. In order to see better as things deteriorated, he climbed the only tree in the area to get the best shots of protesters burning a dummy in the lap of a statue of Lincoln in front of Bascom Hall. His description of the students was so clear, so vivid, that my brother and I may as well have been perched in that very tree beside him. We knew the lighting, the chill of the February skies overhead, heard the voices of people cheering, chanting, excitedly standing together in solidarity. While we had heard about racism and the protests in the 1960s from our own parents, nothing could compare to Will’s retelling of those events.

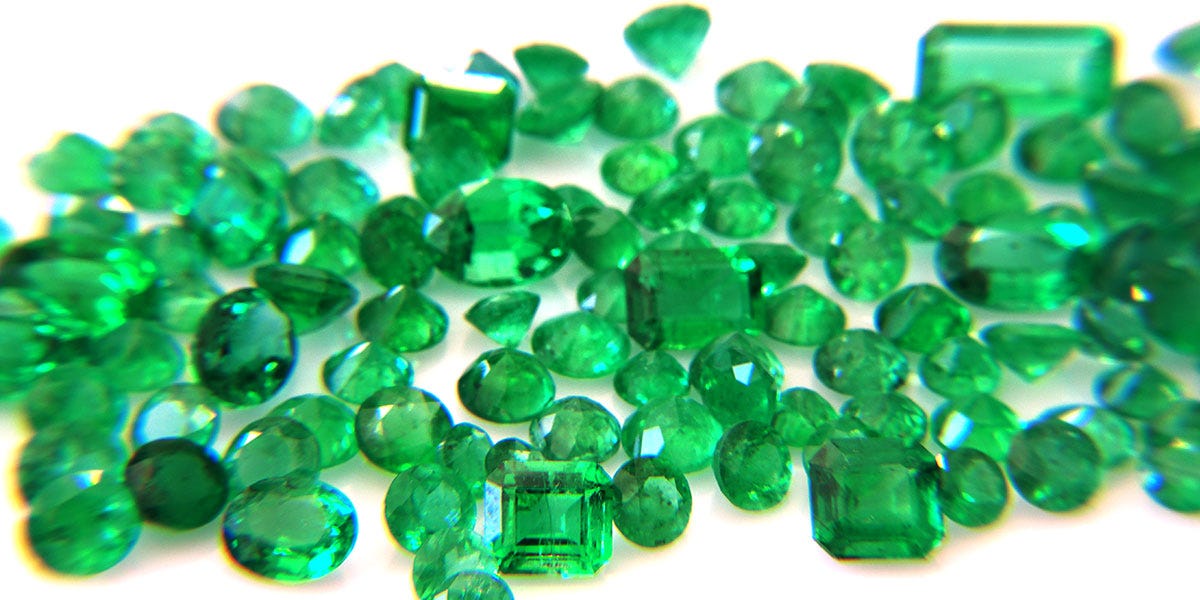

Sometime in the 1970s my uncle found himself in South America. Colombia, to be precise. He had gone – again, likely as a reporter or photographer – for the purpose of working a mundane job, but then things got interesting. He met up with a cartel of great power and influence, and they took him in as one of their own. He took up arms with them in a firefight against a rival, and only a handful of them made it out alive. When I say that his retelling of the guns firing, the smoke in the air, the screams of death and torture all around were more realistic to me than the first time I watched The Godfather, I am sincere. Leaning forward eagerly where we sat on the carpet at his knees, my brother and I stared with open mouths as he explained that he and two other men fled for their lives from Colombia, but not before they split up the stash of emeralds that had been hoarded by the cartel. He knew better than to put them somewhere easy to find when he came back across the border into the US. Oh no, this guy was a pro. He carefully opened the seams of his necktie and placed the emeralds in delicately, stitching around them to secure them in place as he closed it back up. Sneaky as ever, he smiled smugly walking through immigration and security at the airport in Texas. They searched and searched, certain they had a criminal in their hands, only to be thwarted by his superior intellect and tie-hiding scheme.

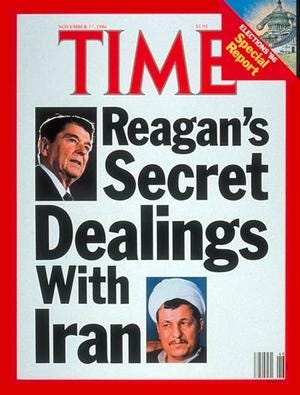

We learned about the Iran-Contra affair on another visit with my uncle. Maybe you’re unaware, but he was pivotal in the sales of arms to the Iranian government. Was he the bad guy? Most certainly not. He was really only involved to help rescue the seven American hostages being held in Lebanon. He was lucky to get away from everything before the government decided to pin it on him. If that had happened, I’m sure he would have found a way to escape.

Because another time, when he was wrongly imprisoned for a crime he (obviously) did not commit, he worked with a handful of other inmates to free himself.

There was also a space shuttle launch that would have ended in death and flames had he not noticed a wire hanging from the side of the shuttle that simply needed to be plugged in.

I can see what’s happening here. You’re staring at me like I don’t know. Like it should be news to me that my uncle, this guy who told these amazing stories with So Much Detail that there is no way he was not there in person for every single event, was maybe not actually there.

I know.

Will was a troubled man. He suffered greatly at the hands of his parents. He was forever an outsider in small towns that struggled to handle a personality as big as his. Focusing was impossible, and his creativity often got him into trouble. He was in prison for a while in the 1980s. Charged with the care of his very young son after divorcing his first wife, my uncle, literally incapable of raising that child, dumped him in the streets of a major city and vanished for over a year. No one knew how to find him. When he returned home asking for help, my grandparents tried to disown him. Clear up to their deaths, they wanted nothing to do with the oldest child they had hurt so dearly, and he could only ever beg for their love and acceptance. When they died, they left him completely out of their will.3

My Uncle Will passed away many years later. He lived in Idaho at that point, in a tiny little mining town. His health declined sharply, and he died younger than he should have. But it was a mercy in some ways. He was tortured by trauma, by things that happened to him as a child and in his young adult life. My mother, his little sister, was the only real family in attendance apart from his wife and adult son. There was no one else left.

“I wish he’d been more normal,” she confessed as we were preparing a very small memorial service for him.

“What do you mean?” I asked, offended at her suggestion that there was something wrong with my uncle. “Uncle Will was cool.”

“He was a liar,” she said coldly. “All those things he told you and your brother? Don’t you know they were lies?”

“No,” I smiled, “they weren’t lies. They were stories.”

“Stories about fake things. He wasn’t at that protest.”

“So?”

My mother could not come to grips with my calm acceptance of an uncle with a wild imagination. To her, it was an affront that he should make up such lavish stories with himself at the center of each pivotal moment in history. But to me, his storytelling was genius.

Will didn’t just talk about an event, he delved fully inside of it. I’m sure in his mind he really was critical in those historic moments. It did not matter to me that his retellings were conjured from his mind, fabricated with elaborate details. They were immersive and beautiful. I would have happily sat through an entire afternoon of stories with him instead of watching TV, which is a big deal to an 80s kid. By the time he was talking about smuggling emeralds, I knew his stories weren’t based off of facts, and I loved him all the more for it. I didn’t need them to be real to be valuable.

I come from a long line of storytellers on both sides of my family. My Uncle Will got it from his own father. My dad got it from his father and his grandfather. These talents have been passed down to me, and I am grateful to carry that tradition on as part of my generation’s gratitude to those who came before me.

My own stories might be like my uncles. Perhaps, like him, I don’t really know which parts are real and which have been created by some aspect of my memory or a misfiring synapse in my brain. The important question is, does it matter? Telling stories doesn’t have to be about truth or facts or evidence. Sometimes it is. But sometimes it is about fiction, about brave, bold ideas, about characters who might not yet exist, about exciting what-ifs. Some stories are about their oration, about the act of telling them by voice to others. They are an art form. They are the celebration of humans passing on tales to one another.

My uncle’s stories were real to me in exactly the ways they needed to be. And if ever I find myself in possession of emeralds that I should not have, I know how to wear a tie through security.

Your trans friend,

Robin

This is actually a super common theme in the Midwest where swimming pools are everywhere, and adults want to keep kids from diving in and getting hurt – they tell false tales of people who were “damaged” by such events.

If my grandfather had lived longer, I am sure our relationship would have deteriorated. He was not friendly to queer people, and I am certain transgender identities would not have been okay with him. So I am grateful to have known him before those aspects of my needed to be shared. This way I have positive memories of him.

My mother knew the wrongness of this and split the estate with him anyway. She defended him many times over, but always with a sideways comment that he was mentally unstable.

A touching story Robin. I'm just speculating here, but I think that since your uncle was a victim of child abuse, he created a little world all his own. A way of coping with the trauma and that was better than his reality.