Running for exercise and joy came back to me in September of 2022. It was one of the most incredible feelings I’ve ever had. It tasted like freedom. But several weeks before that moment, I went for a walk with my wife and our two dogs, and the weather was warm enough that I could walk in just a t-shirt. Nothing underneath.

Nothing underneath for the first time since I was thirteen years old.

I felt the wind gently flowing over the fabric of my shirt, softly touching the bare skin of my back, barrier free. Stretching my shoulders back and down, sternum forward, chin up, I was facing the world as something new, something uninhibited and free.

There’s been a lot of national talk about gender affirming care lately, and so I’m taking this opportunity to talk about the benefits of one of those types of care – top surgery.

A few definitions before we continue

Top surgery in trans circles can either mean a breast augmentation for transwomen and transfeminine folks, or it can mean chest masculinization (or a radical reduction without reconstruction) for transmen and transmasculine folks.1 As a nonbinary transmasculine person I was seeking chest masculinization.

Dysphoria is also important to understand. Not everyone experiences dysphoria, and those who do often have very different feelings about it. Dysphoria is the feeling of disconnect between a person’s internal sense of gender and how they are perceived outwardly by themselves or by others. Dysphoria can make it hard to look in the mirror at your face. Sometimes it makes showering impossible. Voice dysphoria makes it terrifying to answer the phone or speak in public out of fear of being perceived as the wrong gender. Physical forms of dysphoria can impact the desire or ability to leave the house and be social. The emotional impacts of dysphoria include fear, anxiety, panic attacks, depression, and self-harm.

Gatekeeping is the last definition to cover. In the context of gender affirming care in the United States, medical providers will most likely look to the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) Standards of Care (SOC). The most recent version of this was published in late 2022 (SOC version 8). WPATH guidelines help medical providers and patients understand how best to go about obtaining gender affirming healthcare, which can include things like hormone replacement therapy (HRT), various gender affirming surgeries, voice therapy, hair removal, and psychiatric care.

Despite the decades of progress in trans healthcare, there are still a number of steps a person must go through in order to be eligible for hormone therapy or for gender affirming surgeries. In most cases this takes the form of letters from psychologists or other mental health providers in order to access surgeries, hormones, or referrals for other types of care. Sometimes multiple letters are required.

In the specific case of top surgery for transmasculine folks, at least one letter from a mental health provider is required. This is done to assure the insurance company or the surgical team that the individual understands the risks and complications, doesn’t have any current mental health concerns that could interfere with their ability to understand the implications of the surgery desired, and is genuinely in need of the procedure to alleviate dysphoria or to align their body with their gender identity.

Conversely, if a ciswoman is seeking breast augmentation, no letters from mental health providers are required.

Gatekeeping is the activity of controlling, limiting, or requiring significant processes to access something. And, while it could be a good thing in some circumstances, it is utterly absent in companion cases, such as mentioned above.

Choices

The first time I discussed anything close to top surgery with my wife, our youngest was still an infant, and I was (for the second time) struggling with the challenges of breastfeeding. We both agreed that once we were done with lactation we should look into me getting a breast reduction. We didn’t. Life got busy, the kids started growing up, work took over, and we focused on more important things.

But if you had told me in that moment that I could have masculinizing top surgery, I would have immediately said yes to it.

Fast forward to 2022, to me coming out as transgender to my wife and to our families and friends. The very first thing I knew I wanted to talk about was top surgery. To her credit, my wife was on board very quickly. I started looking for surgeons, I joined some discussion groups, did a ton of exhaustive research, and I even consulted my employee insurance benefits to understand the process of getting my gender affirming care covered.

Plenty of choices in my life were never that easy, but top surgery was just this foregone conclusion. It would happen. It needed to happen.

And in the meantime, I suffered heavily.

I tried binding to alleviate the chest dysphoria I was suddenly aware of, and that only made things worse. It drove my anxiety levels up and encouraged panic attacks. And the more I tried to solve the problem, the less I wanted to engage in life outside of my home. I stopped leaving. I was reluctant to walk the dogs where anyone could see me. I froze up and sheltered in place. Going to work in person for just a handful of days drove me into a deep depression.

For more than 30 years I had dealt with having extremely visible breasts by physically caving in on myself, by ignoring and hating my body, and by not dealing with my transgender identity. Confronting those things nearly broke me.

Moving forward

I found a great surgeon to work with, and my top surgery was scheduled for the day of Pride in 2022 (which also happened to be my wedding anniversary, but my wife was very understanding). The only thing I worried about was the covid test the day before. I had zero concerns.

After living with a part of my body that had crippled me for so long, the thought of waking up without it was difficult to picture. And when I did wake up from that surgery, all I felt was groggy.

In the early recovery days post-surgery, I also felt like I’d been cut in half and stitched back together. I joked about being a broken gingerbread cookie. This was my early coping strategy for the fear of being without the Velcro binder wrapped around my ribcage to literally hold me together. I panicked when it came off for dressing changes. But the days moved on, and my body healed right on schedule. Before long, I was up and moving with nothing over my chest but a thin t-shirt and some Band-Aids over my grafted nipples. The swelling reduced over the weeks to come, the scars responded to the gentle massage and daily dose of hydrating gels and creams.

My range of motion was slow to return. I was afraid that moving too much would widen my scars, but I was itching to run again, to use the rowing machine, to lift weights. These are things that ground me, that keep me level and calm throughout the hectic pace of work and life in general.

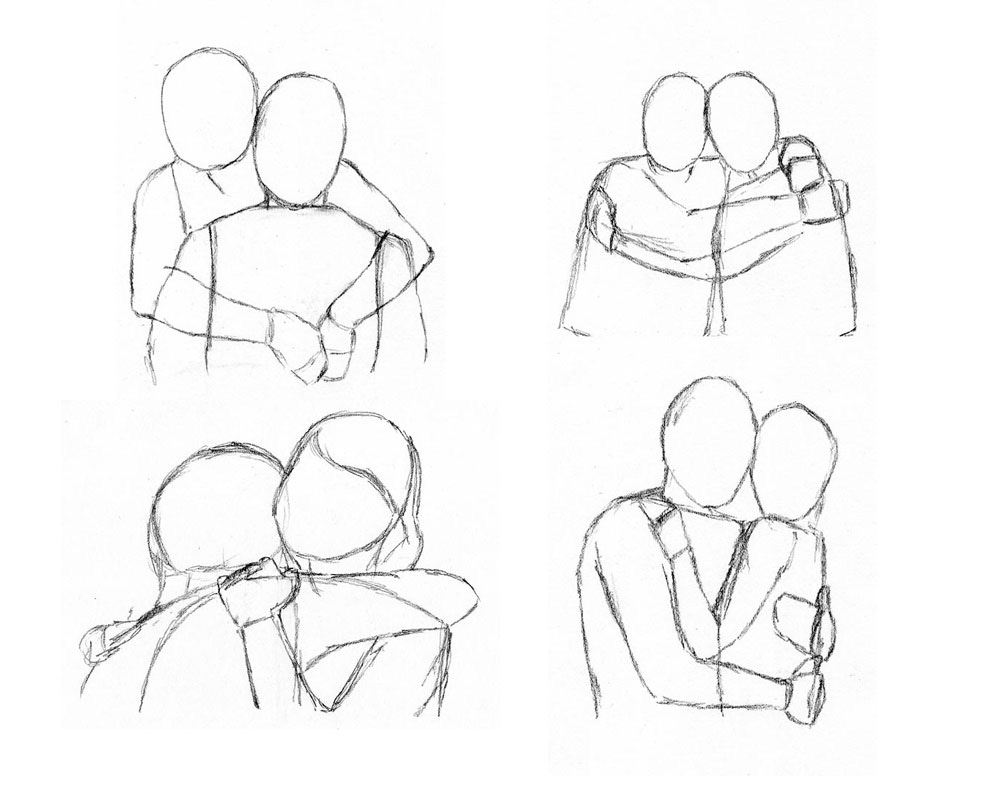

And then something truly miraculous happened. My youngest child fell and got a bit of a scare, and I bent low to gather him into a protective hug. Ask anyone who has seen me parent, and they’ll all tell you the same thing; I believe in physical contact, in providing the security of touch and holding to both of my kids whenever they want or need it. They’d been so well-behaved with me after that surgery, always hugging my arm from the side, never pushing or taking risks around me while I recovered. But as I pulled his body close to mine and encircled him in my arms, I felt him for the first time.

I hugged my son with my whole body.

I could feel him breathe against my sternum. I could feel him laugh once he was happy again. I could feel everything.

I hugged my wife after that – a really good hug like the kind you give when you get off an airplane after a long trip far from home – and my arms wrapped around her like they never had before. I couldn’t get enough.

It became a kind of a party trick, I guess you could say. When I’d go out to see a friend or coworker, I’d ask for a hug, and they would always deliver. And in that hug, I’d tell them how amazing it felt now, now that my body could be close to theirs with no barrier. There was nothing between me and the people that I cared about. I wanted to hug everyone.

I simply could not get enough hugs, and I was really putting in the effort!!

Tangent – I have since gotten more and more strange looks from people when I do my hugging trick. This is toxic masculinity at its finest. They’re giving me all the nonverbal cues that “men don’t hug,” which tells me (in the most ridiculous way) that some of them are starting to see me as a man. And that’s progress. But this will always be a problematic barrier between me and the normalized world of “men don’t hug.” I will be the guy who does hug. And if you’d lived half your life without getting to feel how wonderful a close hug could be, you might learn how great it is to also be the kind of guy who hugs.

True recovery

Months after my surgery, I started noticing that all of the shirts I’d worn before didn’t fit quite right anymore. And it wasn’t a stretched-out chest like you’d think. No, this was about the neck of the shirt resting too high at the base of my throat. It felt like my clothes were choking me. V-neck shirts were the only ones that felt good anymore. The difference? My posture had changed completely.

In the absence of the weight of breasts, my shoulders relaxed, and my upper back let go. Some of it took practice, active work in front of a mirror every day. I spent time visualizing my shoulder blades as wings that I needed to tuck down and back so that I could fix forty years of abysmal posture.

But it wasn’t all posture work. It was also comfort. My body finally fit. My body felt like me.

Walking past a mirror or a glass window reflecting my silhouette was no longer a source of dysphoric discomfort. I could slow down and stare at myself, at the outline of my masculine chest that was – for the first time ever – in proportion with my body as a whole.

“Wow. I look like my dad,” I whispered to myself one day.

My oldest son passed me on the steps of our house not long after, and he stared at me in a way he hadn’t before. “You look like a boy now,” he said in wonder.

“Well that’s the point,” I smiled back. And all I felt was joy. Pure, absolute joy.

Life revised

I run now without thinking about stupid restrictions like sports bras. They all got thrown out a few days after my top surgery was complete. I still marvel at the feel of a shirt over my bare skin, even in the places around my scars where nerve connections are slowly re-growing and numbness prevails. Seat belts fit me right for the first time in my life. Messenger bags don’t need to be readjusted every ten seconds. I can nap on the sand with my chest and belly happily spread out on a beach towel. You might even catch me walking around in just pants or shorts with no shirt at all and a goofy grin on my face.

Top surgery didn’t just save my life, it gave my life back to me. It helped me find something I’ve never felt before: acceptance. Love, even. That deep kind of self-love that I can see when I look in a mirror and smile at myself. I’m sporting a dad-bod, and I am so in love with how that feels.

Your trans friend,

Robin

It’s worth noting here that (first) there is no one way to be trans, (second) there is no one way to be nonbinary, and (third) nonbinary identities do not require a person to conform to androgyny. So top surgery for nonbinary individuals could include reduction, elimination, or augmentation. Last note, some cis-identified people also get top surgery for a variety of reasons that are not always cancer related. In other words, this is a popular procedure for a wide group of people.