Try, if you can, to imagine a nearly-six-year-old version of me. Conjure up the image of a child who was probably smaller than average, quieter than average, and oddly creative about the inner lives of inanimate objects. Think Velveteen Rabbit or Toy Story concepts… where a kid intuitively knows that their toys experience very real lives but are bound by secrecy around humans and can never be seen moving or breathing or engaging. That was my world. And that world was filled with plush friends.

As a kid of the 80s my religion was Cabbage Patch Kids, My Little Pony, Strawberry Shortcake, Rainbow Brite, Transformers, and absolutely He-Man and She-Ra (though nowhere near as good as the modern rendition of She-Ra by ND Stevenson). And let’s not forget, Care Bears™.

My seventh birthday, the year after this tale, was a Care Bears™ themed party. Care Bears™ cake, Care Bears™ decorations, I know that I wore a Care Bears™ dress (which was essentially a t-shirt with a skirt attached, but gorgeous nonetheless). And crème de la crème, my friends and I sqee’d with delight when my dad took us into a theater to watch the Care Bears™ movie (don’t worry, he suffered then as much as I now suffer when “required” to watch something my kids gush over). The point? Care Bears weren’t just a cultural phenomenon, they were personal. I was a huge fan.

Lucky, which is a very original name for a green Care Bear with a four-leaf-clover on its belly, was a gift from my parents. Care Bears came in two sizes that year (we’re talking 1984, give or take): regular size and pint-size. Lucky was the smaller version, just big enough to need two child-sized hands to wrap confidently around his belly as I hauled him everywhere I went.

And we went to St. Louis. The reasons were boring.

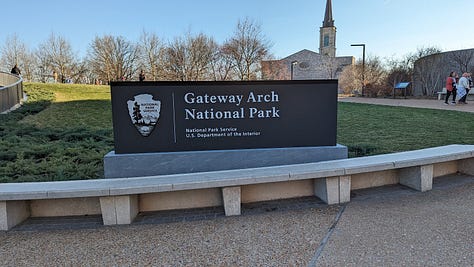

Children are often toted along on journeys by parents with few other choices. I’m certain my mother resented having to bring me and my brother, but my memories of the trip center more on the enormity of the St. Louis Gateway Arch. It looms as a giant in those hazy glimpses of my childhood. I don’t recall the park where it was built or the exhibits we surely looked at before riding in the terrifying pods up to its lofty viewing windows more than 600 feet in the air.

I recall my mother’s hand holding mine as we ascended. I recall Lucky in my other hand.

Here is the aside I did not expect to write along with this story – My mother is no longer part of my life. This is not due to death. It was in fact my own choice. If I were to speak these words to you, you’d hear the tremulous shame I now carry over this decision. But you’d hear my resolve, too. You would hear regret and sorrow, you would hear self-comfort and stillness.

Sitting in that tight metal pod, following the arc path up that iconic structure, my tiny hand tucked securely inside my mother’s grip, I must admit to you that I don’t know if she comforted me. I don’t know if she told me that I was safe or that she would always be there to hold my hand. I don’t recall her words or actions, and I might be inventing the part about her holding my hand. Perhaps that’s the memory I want to have. Perhaps that’s a truth I built to protect myself. You’ll never know the difference, and neither will I.

But I know with certainty that I held Lucky, and he held me back.

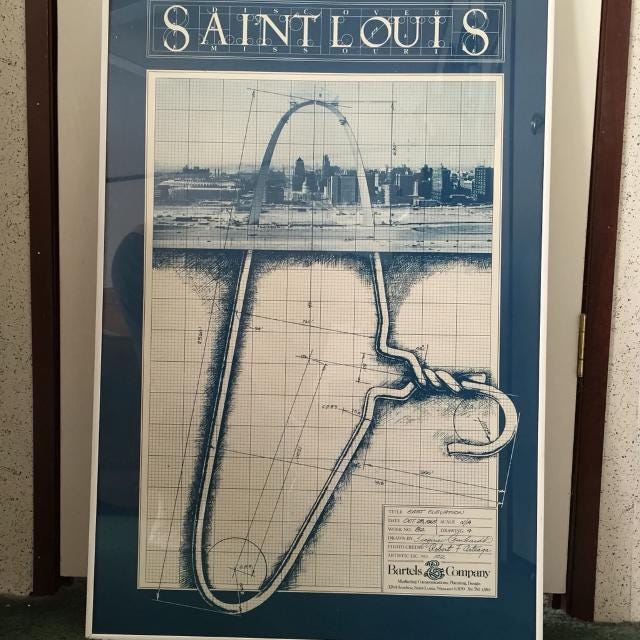

I do recall staring out over the breadth of the city of St. Louis, over the river and the buildings and the roads. There was a piece of art in the gift shop that also stands out clearly in my mind, a rendering of a coat hanger embedded deep in the earth, one end protruding as the St. Louis Arch. (Siegfried Reinhardt)

On that same journey I was required to attend a seminar and stay quiet “while the adults talked.” And that was the entire reason for the bribe that was Lucky. No resistance came from me. Lucky was more than enough entertainment.

When children grow up around the isolation of a parent facing mental illness they are often required to build their own worlds to explore, to engage with, and to find comfort within. I took to such activities with great excitement, and Lucky was a new friend to share those worlds with. Lucky didn’t mind that I came from a poor family or that I didn’t have other friends. He was happy to read quietly with me or to whisper secrets back and forth under a fort of blankets and pillows. We could imagine adventures together. We invented our own stories. And when I stared into Lucky’s beautifully embroidered face, I knew we would build years together out of that friendship.

But right at the end of the seminar, I placed him on the floor beneath my folding chair. We got up and left, and I cried once we were in the lobby. I knew I had left Lucky behind. My mother marched back into that enormous room, and together we searched every inch of it for my friend.

He was gone.

I can’t explain to you why that event was so singular that I have carried those memories with me for forty years, but I’m not making it up – I have told many close friends about that loss in vivid detail, especially if Care Bears came up as a conversation topic.

Partway into the beginning of my cross-USA road trip with my friend I brought this story up. And at the end, when I explained just how much of a hit it was to lose that little bear, he looked at me and said (with utter certainty), “We’re going to find Lucky on this trip.”

I laughed dismissively.

And it was just a day later, somewhere in a tiny corner of Kentucky on our way toward St Louis and the Gateway Arch, we stopped at a diner for lunch. On the way in, we went through a little shop, and I walked right past a self of souvenirs and toys. My fingers brushed against the collection of stuffed animals at hip level, and I glanced down to see a little green bear with a four-leaf clover on his belly, a tag of authenticity punched through his ear.

It was Lucky.

Lucky had been waiting for me to show up. Right in that moment. Right in that bizarre place I’d chosen for lunch that day.

I picked him up and stared at him in awe. He sat on the table as I ate my stew, he waited patiently while we paid for him, and I held him once we were back in the car and on our way to Missouri. Somehow, after forty years, the universe aligned in just the right way to bring Lucky back into my life.

I don’t really put much stock in people being “too old” for toys or stuffed animals. Comfort and joy don’t have age minimums or maximums in my book. I’ve mentioned before that I still have (and sleep with) my blanket from childhood. I actually have several of these little treasures, most of which have been commandeered by my children over the years. So of course when I made my way home to them, the kids immediately thought Lucky was a gift for them. I declared him off limits.

How often do we get the chance to close the loop on childhood events that left us traumatized or feeling grief and loss? How does a stuffed bear wait that long for its friend to show up? And how does any of this work with the unlikelihood of me [a PNW guy] driving across the country from Florida to Washington in a minivan and randomly stopping at a restaurant in Kentucky?

But also, what was Lucky doing for the last forty years??

It’s difficult to describe how it feels to access emotions that 6-year-old me locked away so long ago. Visiting St Louis after all those years was fulfilling in unexpected ways. It’s a beautiful city, and I would have loved to stay longer to see more of it. Riding up the side of the Gateway Arch, this time as an adult, brought back the fear of being closed into that tiny metal pod and swaying gently as the mechanism ratcheted us up 630 feet into the air. But both of us, little me and current me, both enjoy adventure and seeing new things, and we were both present in a way that would not have been possible without finding Lucky only an hour beforehand.

There is, sadly, still a theme of loss that comes with Lucky’s story. For now it’s nice to appreciate having him back in my life and sitting in a place of honor in the house. Letting go of childhood is often a very real, physical process, wherein many of us lose possessions, photos, and touchstones of family life due to our separation from those family units as queer teens or adults. I didn’t mean to leave Lucky behind, and maybe I wasn’t supposed to after all.

This isn’t the space where I meant to admit the loss of my mother, of my father too, but I think it’s relevant, and I know I’m not the only person here who has chosen to remove themselves from trauma, toxicity, or unsafe relationships. I miss both of my parents deeply, and it’s not a simple topic to write about. Lucky gives me an avenue to walk down that allows that pain to be present without overwhelming me, which is part of the healing process. If you have similar pain, don’t give up looking for your Lucky. Maybe he’s waiting in an unexpected place. Keep your eyes open.

Your trans friend,

Robin

Robin, perhaps Lucky was out having happy adventures in the world at a time when you couldn’t and now shares them with you when you’re asleep and dreaming.

This brought tears to my eyes, Robin. Take care of yourself, and Lucky too.