It was forbidden, which – to any six-year-old child – means it was irresistible. Allow me to describe it; shiny red paint, a two-piece chrome BMX handlebar, wicked knobby tires, and a seat that Dad promised to lower for me. Eventually. Once I was old enough for it.

I am the younger sibling. My big brother was my idol. Sometimes he still is. It was his bike, and what always happened with his old things? They were handed down to me, of course. For a kid like me, there was nothing better than inheriting my older brother’s clothes and shoes and toys. If I could have gotten my wish, I would have grown up to be just like him. [In retrospect, kids seem to be pretty horrible at picking out idols.]

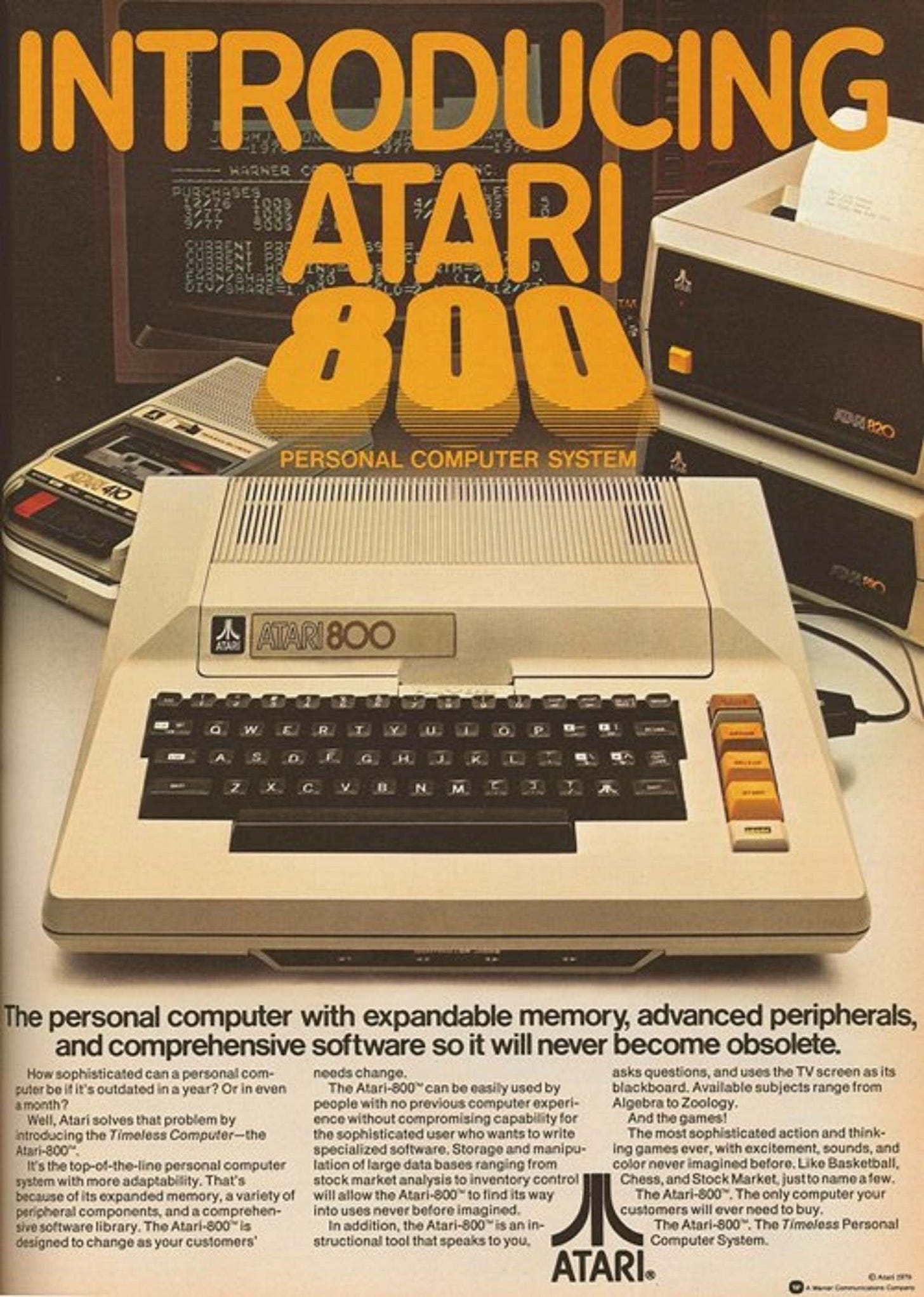

A few Christmases earlier, our parents had bought my big brother an Atari 800 video game console. It was one of several that we would upgrade to over the years, but it set the tone that my sibling would always get the cool stuff, and I would get them once he had worn them out (but not too much). This arrangement suited me just fine.

Tired of playing Frogger? I’ll take that, thank you.

Done with your posable He-Man action figures? Gimme.

Did you outgrow those acid-washed jeans? Mine, yes.

The bike was another matter altogether. As a poor family in the Midwest surviving on one parent’s salary as a minister in the neighborhood church, new stuff wasn’t the trend. Everything we got was used. This wasn’t just for me, it went for my brother, too. I couldn’t tell you where his super-cool BMX bike came from, but it wasn’t a new purchase. Neither was the stupid pink sidewalk bike they’d gotten for me a couple of years earlier.

Allow me to choke back the bile from my memory to describe the beastly instrument of my undoing.

It was pink. I despised pink. Pink was girly. It was baby dolls and Barbie and “aren’t you sweet for helping your mommy in the kitchen,” and this was way before anyone thought to use pink in making Lego bricks. The pedals and seat and handlebar grips were white. I don’t know who came up with white as a color for those things, but they don’t stay white. I believe there were also sparkly streamers at the ends of the handlebars on each side. And training wheels. It had training wheels. Those were for babies. Everybody knows that. Top it off with the notion that my parents called it ‘a sidewalk bike.’ That meant I wasn’t road ready. It meant I was the baby.

A bicycle is often the first tangible feeling of independence for a child. Once you gain enough balance, confidence, and speed, you can outpace your parents, zip through neighborhood streets shocking the old ladies watering their flower beds, and even make it past the mean neighbor’s yard with the angry dog. A bicycle is freedom.

And I craved freedom.

Late at night I crept to the landing of the staircase and eavesdropped on the conversation between my parents.

“You really think she’s big enough to handle it?” said my mother’s worried voice.

“She’s been asking for that stupid thing for weeks. Let’s just do it,” my dad grumbled.

“The seat is too high for her to reach the ground.”

“I’ll lower it.”

“When? You hate using tools.”

I only heard a grunt after that. He really did hate using tools. He still does. And I know I could have waited, but how many six-year-olds do you know of who are good at that?

Early the next morning, stomach full of pancakes, heart in my throat, I crept outside “to play.” I moved cautiously toward the garage. Every creak of the side door set my nerves on edge. I knew I could be discovered at any moment, but the thrill overrode any common sense I possessed. And so I pursued my target with a newfound bravery and determination that would later lead me into so much trouble in life that literally everyone I know rolls their eyes at its presence.

There, resting against the wall next to the car, was the bicycle of my dreams. It wasn’t just my big brother’s bike – it was a BMX bike. A dirt bike. It was the very symbol of boyhood, of a masculinity I secretly craved and could never confess to.

It was cool.

It was fast.

It was mine.

I freed it from its sad existence of neglect beside the new bike my growing sibling had been given, and I purposely avoided making eye contact with the pink bike nearby. It wasn’t worth my attention. Together, cool bike and I strode out into the summer sunshine to face a world of possibilities.

There was only one problem. I really was too short to get my butt on the seat.

Not to worry. With the knowledge that I was always smaller, slower, lighter, or something lesser than my older brother, I had gained an ability to climb, twist, contort, and use tools like a crow does to manage the enormity of the world. I maneuvered the bike to the side of the house where a grassy berm aligned with the sidewalk (yes, the sidewalk I had always been confined to until this moment). The little hill there rose steeply to my right, tires set just at the boundary between grass and concrete, and with one foot on the hill and the other on the left pedal, I could just find my way to the security of the saddle under my bum.

I was in business.

My hands twisted the black rubber handlebar grips. My voice rumbled with the sound of a motorcycle engine. My stomach twisted in knots at the possibility of falling and scraping my bare skin (it was a hot summer day, after all), but risks are part of life, and I was older and wiser now. Maybe I had even grown half an inch in my sleep that night. I was ready.

“Hey. Neighbor kid’s little sister.”

I looked up to see the slim form of the neighborhood big kid, Andy. (Ironically, he was riding a Huffy ten-speed road bike that my parents would later buy from him for ten dollars, and I would end up ramming it into the back of a car nearly twelve years into the future. But alas, that’s another bike story for another day.) Andy was excellent at mocking every other kid in the neighborhood. He was older. He was taller and stronger, and he could ride fast. I’d seen it.

“Isn’t that your brother’s bike?”

He didn’t know my brother’s name any more than he knew mine. “Nope. It’s mine now. I grew.”

“You know how to ride that thing?” He struck a cool pose in the street, one leg aloft on a pedal.

You’re thinking I should not take the bait. I agree. But clearly… “I can ride faster than you.”

“No way. Prove it.”

“I’ll race you.”

“Where?”

I stared off into the distance, a practiced look of examining the course on my wizened six-year-old face, emulating the very finest drivers from the Indy 500 we all watched every year on TV. “Through the parking lot, around the back side of the school, past the loading dock, finish line between those two trees,” I pointed.

For those of us who grew up in the 1980’s there were few things that could settle a dispute like a bicycle race. It was a common system of rank establishment, and the rules were clear without ever having to be stated.

First one to the finish line wins.

And that’s about it. We didn’t engage in any wild tactics to push or hurt anyone, there were rarely collisions, and there was always somebody to stand at the finish line and wave an arm like the checkered flag at the conclusion of a big race. But this race was different. It was just me and Andy. Nobody else would know. Nobody would witness it to talk about it for days or weeks or months to come, and I think Andy knew that. I think he was afraid.

“Ready, set, go!” he said, and I was off in a blaze of muscle power and fury.

And good god, that bike could really move! No clatter of training wheels in my wake, no streamers to slow down my aerodynamic form, just me and the simplicity of the coolest bike I had ever seen under my body rocketing through the asphalt parking lot of the local elementary school that happened to sit next door to my house. The trees and playground equipment were a blur. My speed was intense. No one had ridden a bike with such ferocity.

Best of all, Andy was nowhere in sight behind me. I’d heard his labored breathing at the start, but then he faded from my glorious contrail of dust and summer pollen. I was alone.

I screeched hard to my left to wrap around the elementary school building, through the parking spaces reserved for faculty during the school season, and I rose up onto my feet to add more speed. Who needs a seat anyway? There was no time to coast. (Also ironically, most parents lower their kids’ bike seats so much that they can touch the ground with flat feet, but it prevents a full leg extension during pedaling, which could explain how I managed to eke out Mach one on that beautiful machine.) Left again, this time taking me behind the school, and Andy was a distant memory, a faded ghost with no chance to catch me. One more left, and I blazed past the loading dock where we dared each other to jump off and endure the blazing pain up our lower legs at the end of the each long, hot Midwest summer.

At the entrance to the school, I whipped right to line up with the road in front of my house where the two oak trees stood guard over the parking space where my mother often left our classic Honda Civic hatchback after grocery trips. Between them was a heavy layer of crushed gravel, the perfect location for the conclusion to an epic race.

My legs burned with lactic acid. An ache was building in the palms of my hands from the sweat and strain of each pump diving me forward. Breath came hot and dry over my lips and into scorched lungs. But I knew with no hesitation that I was going to win.

I was going to beat the snot out of Andy and his smug attitude.

There are two types of brakes on most kid bikes: coaster brakes and rim brakes. Rim brakes come with a lever on the handlebar, and that requires some coordination and grip strength. So back in the 80’s, coaster brakes reigned supreme. With a coaster brake, you pedal backwards a quarter turn to engage a full stop of the rear axle. There are no degrees in this kind of braking system; it’s all or nothing.

Sensing that my velocity was excessive at the very moment I crossed the finish line on the gravel space between those two enormous oak trees, I engaged the coaster brake by slamming my foot backwards. But the gravel liquified under my tires, and my momentum drove me straight into the event horizon of that tree, that sucking black hole of force that claimed, first, my shoulder, second, my face.

I bounced.

I bounced clean off that damn tree, the bike falling one way, my body the other. The impact had knocked the air out of my chest, and I squirmed in the gravel and dirt with pain and a deep need for oxygen. By the time I pulled in a lungful of air, the panicked face of my brother was over me. He screamed out, "She's dying! She’s dying!” again and again until my mother came running.

She carried me into the house, ice applied to my face, a cool, damp rag over the scrapes on my arms and legs to soothe me before the inevitable hydrogen peroxide treatment. I was a mess. There was no part of me left uninjured, and that was perhaps my first glimpse into what life in my forties would feel like (everything hurts and I’m dying). I’m sure I cried. And I had not even seen what happened to my face.

This story has come up many times in my life, but mostly when people get to know me well enough to ask about the scar(s) on my upper lip. That’s when I tell them about the two times I crashed a bike into a fixed object, always leading with my face. The first scar was from the incident at six on the bike that was in transition between my brother and me. The next happened when I was eighteen, and I scarred the same stupid place all over again.

Scrapes and cuts and bruises tended to, the biggest concern was that I had collided with a tree using my head as the blunt instrument. My mother was obviously worried about a concussion. She packed us all up and drove us to the local hospital. It wasn’t until we were home that afternoon that I finally saw the incredible purple bruising around my right eye. It consumed half of my face. I sustained no significant damage apart from that, but neither did the bike or the tree. The tree lost a piece of bark. The bike was just as epic as ever. I wasn’t allowed near it for two weeks, during which time I was grounded.

As for Andy, I can only tell you my end of things, as he would never confirm them when confronted by my parents. He lost the race. So, of course, he lied about being there in the first place. He denied seeing me. He had no memory of the event at all. And really, what self-respecting older, bigger kid could ever admit to getting their butt whipped by a six-year-old on their big brother’s bike? Maybe he laughed off the race entirely and left once I was through the parking lot. Maybe he fell down and skinned his knee and couldn’t bear anyone seeing him cry. We’ll never know the truth.

But what do we know for sure? I crossed the finish line first. No question about it.

Lessons learned…

Everybody wants to hold you back.

Always watch out for the little guy if he’s got a hill to put a foot on.

Don’t wait for others to adjust the seat height when the world is waiting for you to race through it.

Challenge the big kid.

Pedal hard.

Maybe don’t create a finish line in gravel with a huge tree at the end.

Hey, thanks for reliving the early 80’s with me. In exchange for all that epic awesomeness, comment and tell me about how you broke the rules to become the cool person you are today.

And if you haven’t already, subscribe so you don’t miss any of my other I-ran-into-a-fixed-object-with-my-face stories.

I skidded out on gravel in front of all the big kids once, massive road rash, and I was so mortified with embarrassment I didn't cry. Apparently, the fact that I just stood up, got back on the bike and rode home was the stuff of legends, and those big kids still talk about it to this day.

This is a great story and its this kind of accident as a kid probably why I could never breathe properly from hitting my nose and only getting it corrected 30 years later. I am sorry for not being a great person and understand the block. Even though I dont know you I had been thinking about you. Blocked as well on my birthday of all days. Well you're a cool dude and sorry to have caused you grief.